Militia units from surrounding towns faced the angry crowd. The militia captain demanded, “Who is your leader?” The entire crowd shouted, “I’m the leader!” This confrontation might bring to mind a famous scene from the 1960 film Spartacus. But it actually took place on March 7, 1799 in Easton, PA., during what is known as the Fries Rebellion.

The Fries Rebellion was one of many, like the Shay’s and the Whiskey Rebellions, that immediately followed the Revolutionary War. These uprisings rose from tensions between Revolutionary ideals of egalitarian self-determination, and problems of nation building with a centralized power structure. In post-Revolutionary terms: (egalitarian) Republicanism vs. (centralized) Federalism.

The Fries Rebellion occurred in German communities of Pennsylvania’s Northampton, Montgomery, and Bucks counties. German immigrants had been near the bottom of the social ladder since establishing themselves in the area several decades earlier. They were drawn to the fringes of colonial society by the allure of freedom from impoverished servitude back home. Pennsylvanian Anglicans and Quakers, however, considered them ignorant, lawless, and alien.

Along came the Revolutionary War and it’s egalitarian promise. Here was a chance to socially advance by joining the cause, enlisting in the Continental Army, and proving themselves as patriotic – and equal – citizens.

The Fries Rebellion, like Spartacus’ slave revolt, was quickly put down. Unlike Spartacus, who was nailed to a pole by the Roman army, the Fries Rebellion’s nominal Republican leader John Fries (the whole point was that there should be no ‘leaders’) got a presidential pardon by Federalist John Adams. Furthermore, the status of German communities continued to grow.

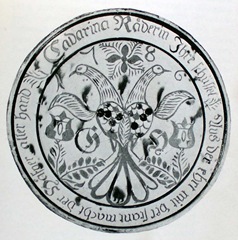

As Germans fought to secure a place in the new order, they began proudly displaying their ‘German-ness’ for all to see through quilting, illuminated manuscripts, furniture, and other decorative arts.

This was the heady environment that witnessed the flowering of Pennsylvania sgraffito redware pottery, or “Tulip Ware” as it has become affectionately known. Yes, Tulip Ware is flowery, ornate, and pretty. It also denotes pride and determination in the face of discrimination and disrespect. There was no need for individual leaders in that effort, either.

Reading:

Many Identities, One Nation, The Revolution and It’s Legacy in the Mid-Atlantic. Liam Riordan. University of Pennsylvania Press/Philadelphia. 2007.

Tags: Fries Rebellion, John Adams, John Fries, Redware, Revolutionary War, sgraffito, Shay's Rebellion, Spartacus, Tulip Ware, Whiskey Rebellion

August 28, 2016 at 12:05 pm |

[…] spin-offs. We’ll settle for now with an observation of possible interest to Pennsylvania ‘Tulip Ware’ […]